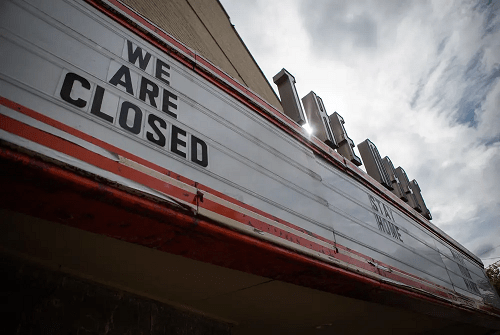

The Marc, a nightclub and venue in San Marcos, closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo credit: Eddie Gaspar/The Texas Tribune

4.16.20 – Texas Tribune

Many businesses without accountants, lawyers or other professional help failed to get their applications in for the Paycheck Protection Program funds before the money was depleted.

In the era of lockdown and economic collapse, not all small businesses are equal.

Across Texas, owners of small engineering firms, retail shops, restaurants and countless other enterprises were in a Darwinian scramble to stay afloat in recent days as they competed for a piece of a massive federal forgivable loan program to help keep employees on staff and fend off further economic meltdown from the COVID-19 pandemic.

But the capacity of businesses to swiftly secure that money often depended on their financial sophistication and the support of high-priced accountants, bankers and attorneys. And on Thursday, the money ran out.

Texas small-business owners interviewed by The Texas Tribune described the process as evolving and confusing. Now that the fund is depleted, it is existentially terrifying.

“You are flying solo. … It’s basically beating on the door,” said Tamara Morton Johnson, a chemical engineer with a small business tied to the oil and gas industry in Houston. “Each bank has its own rules and its own guidance.”

Such a conundrum was not the intent of the legislation that created the program and illustrates the scale of havoc the new coronavirus has wreaked on American life.

The primary objective of the loan program was to move as much money as quickly as possible into the hands of small-business owners. As part of the $2 trillion CARES Act, congressional leaders and Trump administration officials set aside almost $350 billion for small-business owners in forgivable loans.

The majority of that tranche went into a pot known as the Paycheck Protection Program via the Small Business Administration. The aim was to prevent small businesses from laying off workers and to keep the American economy from choking as businesses were forced to shut down in compliance with social distancing rules.

Attempts to get the money out quickly have been a smashing success. That $350 billion went out the door in less than two weeks. The problem is this is such a unique program that there was no bureaucracy in the federal government to handle the task. So Congress and the Trump administration devised a plan to have banks loan the money to small-business owners, with the federal government backing them up.

What has become clear in that process is that small-business owners have vastly different levels of sophistication, and federal government aid often depended on how strong of a preexisting relationship a businessperson had with a bank.

For instance, some small-business owners have bankers, accountants and attorneys available who put them at the front of the line in applications. Those helpers quickly produced proactive advice, reassurance and years-old paperwork for application compliance.

Even before the rules became public, many bankers proactively reached out to clients with updates or clarifications on how the federal government might dole out the money. As such, many small-business owners were able to move their applications through the system and are already receiving their loans, which in all likelihood the federal government will eventually forgive.

At every turn, those small-business owners encountered obstacles to applying for loans.

Roadblocks emerged over seeming technicalities, like using personal checking accounts rather than separate business accounts for their companies, or their banks not having relationships with the Small Business Administration. Others feared they were disqualified because they hired subcontractors rather than salaried employees.

Now they’re out of time — at least for now.

With the collapse of the energy market, Johnson’s company is feeling a double whammy of economic hardship. For years, she has run a nimble operation that deals with rubber and plastic molding. She is doing everything she can to continue paying her team. But despite hours of paperwork, she didn’t apply before the money ran out because she has yet to clarify whether her business qualifies for a PPP loan.

She said she found the Houston Small Business Administration office to be highly responsive, and she looks forward to attending a virtual seminar that her federal representative, U.S. Rep. Lizzie Pannill Fletcher, D-Houston, is hosting Friday. Johnson continues to pursue her options in hopes that she qualifies and more money comes online.

Janie Barrera, CEO of LiftFund, a San Antonio-based nonprofit that supports small businesses, said the onus of helping struggling small-business owners navigate the process has fallen on organizations like hers.

“We’re helping them maneuver through the system,” she said. “That’s what LiftFund’s role is, to help people maneuver this system. We’re right there, holding their hands.”

On Monday, her group got a boost.

Within 24 hours, requests overwhelmed the $25 million allotment. In one day, LiftFund received 1,500 applications with requests totaling $1.6 billion.

“We were only able to get nine loans approved, totaling almost $800,000,” she said.

Then on Thursday, the SBA money ran out.

U.S. Rep. Kevin Brady, R-The Woodlands, the top Republican on the House’s tax-writing committee, acknowledged those businesses’ struggles Thursday morning.

“Most small businesses have a local banking relationship of some type,” he told MSNBC. “That was the key to moving these dollars out. Is it a perfect system yet? No, because our economy is complex. Our small businesses, in how they’re structured, are all a little different.”

Lawmakers in both parties acknowledge that more money might be needed for the fund.

“We’re hearing concerns locally that there won’t be money for them, especially in the minority community, in those underserved communities where not every business has that banking relationship,” he said. “That’s why the extra $250 billion the president has asked for is so crucial. We can’t leave them out.”

“It’s not that we don’t share the values of small business, we do,” U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said on a conference call with reporters Thursday. “We have been their champion. … But in order for them to succeed, people have to be well. … People need to be safe, and we need to have the state and local [funding].”

Pelosi added that while only the SBA money is depleted, the other funds will soon be out of money as well, and what’s left has already been allocated.

U.S. Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, countered that logic.

“There’s just no sense of urgency [from Democrats], apparently, when it comes to these small businesses that need this lifeline known as the Paycheck Protection Program,” he said. “And so they’re holding that hostage in order to get other unrelated spending. We’re going to probably have to pass additional legislation when this crisis passes and when we get back in session after May 4. But now is not the time to obstruct the money for the Paycheck Protection Program just because you have other demands you’d like to make.”

The paralysis is not total. Pelosi and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin have, by most public accounts, struck up a productive negotiating relationship, and the outbound money is saving businesses across the country. But complications remain. With each legislative step taken to pass the first bill, the process often took days longer than anticipated. And once leaders strike a deal, passing legislation through Congress while it’s practicing social distancing could be complicated.

Every day of delay is a day closer to a small-business owner somewhere in Texas missing a rental or mortgage payment — or worse, it’s a day when a businessperson decides to lay off staff or close up shop altogether.

Johnson, the chemical engineer, says that even amid frustration and distress, she intends to focus on the big picture. While frustrated, she said she is grateful that a program like PPP exists. And she notes that other Texans are facing far more dire and worrisome circumstances than she is.

Sam Manas contributed to this report.

Disclosure: The Texas Tribune applied for one of these small-business forgivable loans via the Paycheck Protection Program.