5.22.22 – Item Online – Austin

As breaks in the global supply chain continue to impact major industries, Texas lawmakers are looking for ways to lessen the burden, including investments and opportunities to onshore critical industries.

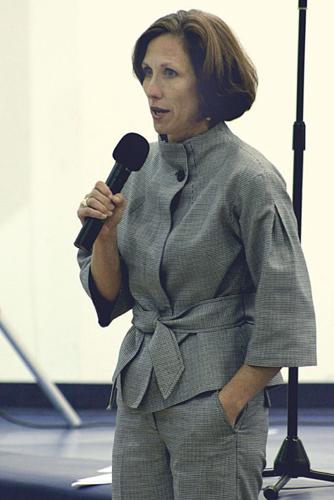

“This is a real opportunity, as you see the supply chain being interrupted, for us to remake America in a way, and as you say, restore near shore,” said Sen. Lois Kolkhorst, R-Brenham. “It’s a real opportunity for America, and specifically Texas.”

The interim Senate Committee on Business and Commerce met Wednesday to speak with industry leaders on ways the state can improve current barriers. This included addressing slowdowns in semiconductor manufacturing and low workforce in trucking. But one message was clear: Real impact takes time.

For example, when it comes to semiconductors, the time between shovels in the ground to physical products can take years, said Chris Bryan, director of communications and information services for the Texas comptroller.

Even as Gov. Greg Abbott touts the recent recruitment of semiconductor manufacturers to the state, those too will take years until chips are made. Two of the largest investments — Samsung’s $17 billion chip plant outside of Austin and Texas Instruments’ potential $30 billion investment for possibly four fabrication plants – will not be ready for production until late 2024 and 2025, respectively.

A lack of semiconductors is particularly worrisome to industries because they are an essential component of electronic items such as computers, health care devices and auto parts. The current global shortage on chips is driving up the prices of goods.

Bryan said attracting these businesses is a vital first step, and legislators can help foster it through reduced regulations. But state lawmakers must also focus on training a workforce for these jobs.

“Policies that support training and creating a pipeline for those critical jobs, and providing whatever support is appropriate for that, will help ease (issues),” Bryan said.

That includes other critical jobs in the supply chain such as truck driving — which is currently 80,000 drivers short — and cyber security professionals, as well as investments in infrastructure and digital tools that can help address bottlenecks, he added.

Bringing semiconductor companies to Texas will not be enough, said Edward Anderson, business professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

Manufacturing the chips is only one part of making a laptop or piece of medical equipment. If other components are delayed, the item is stalled.

“This was a problem even before the pandemic; (the) pandemic just made it worse,” he said.

Anderson added that beyond manufacturing, there are other operations before and after a chip is produced. If Texas truly wants to onshore production, that would include acquiring assembly and packaging firms – both of which take enormous capital – as well as the chemicals needed to build the chips themselves.

“There are other things — on both sides of that supply chain — that are mostly located in Asia still. Getting those companies into Texas actually is probably more important at the moment than getting more semiconductor manufacturing, because we’re doing a good job there already,” he said.

Committee members will take the recommendations for potential new legislation during the next session.

Anderson said that however lawmakers decide to address the issue, it will take time.

“What I would say is that to ameliorate some of our supply chain concerns is not a short term. There are no short-term solutions,” he said.