Just three months after an Anne Arundel County Public Schools special education student died after choking in a special education classroom, Maryland lawmakers are considering a bill that would mandate surveillance cameras in all special education classrooms by the start of the upcoming school year.

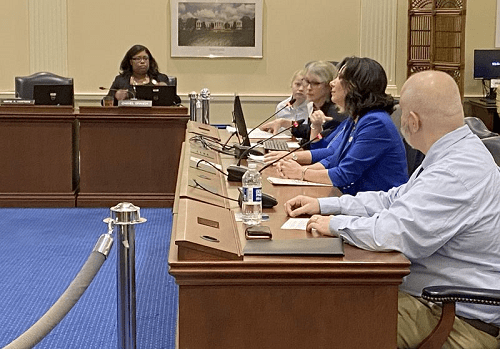

House Bill 1292 would require parents to be notified of the cameras’ existence and for signs to be posted in clear sight outside each classroom. The intent of the bill is to protect special education students, said its sponsor Del. Michele Guyton, a Baltimore County Democrat. It is opposed by the Anne Arundel school system, the Maryland Association of Boards of Education and the ACLU of Maryland.

The hearing was held several months after Bowen Levy, a student at Central Special School in Edgewater, died after choking on a latex glove. His father, Bryan Levy, did not testify Wednesday. In an interview with The Capital, he declined to take a stance on the bill because he worried he didn’t have an informed opinion of the advantages and disadvantages.

He did raise concerns about pouring resources into surveillance cameras rather than personnel.

She described several incidents in which her child came home from school with injuries — including a broken leg and a missing tooth — that teachers couldn’t explain. She said she would have answers if Destiny’s classroom had surveillance cameras.

“I can tell you where it didn’t happen,” Reinhardt said. “Her break did not happen in the hallway because there was a camera there and they were able to look at that. If only there were a camera in the classroom … We were told to move on.”

Bob Mosier, Anne Arundel schools spokesman, said he was unable to comment on student-specific cases.

“While a parent or guardian may wish to have access to view video of his or her child, such video will almost certainly contain images of other students. That is problematic from a privacy rights standpoint, and the fact that other students whose images and actions may appear on the video may be receiving special needs services creates an additional concern,” Mosier wrote in an email.

“While a parent or guardian would certainly well understand the special needs of his or her child, that parent or guardian has no firm right to view another child who may be receiving independent services.”

Mosier said the county schools also oppose the bill because it doesn’t have attached funding.

The bill’s fiscal note says funding for cameras should come from local governments and school boards, not the state.

Toni Holness, public policy director of the ACLU of Maryland, said this type of video surveillance “is problematic because parents and families of children with special needs are not given the opportunity to opt-out of the proposed surveillance.”

Holness also voiced concerns about racial equity.

“Although it may not be the bill’s intent, historically, surveillance has disproportionately disadvantaged children of color and children with special needs, whose behaviors may be recorded and penalized at higher rates than their white counterparts,” Holness wrote in a statement. “We would support alternative approaches, including investment in training and cultivating teachers, mental health professionals, and support staff who treat our children with respect.”

Lawmakers have not yet voted on the bill in committee, which is standard following hearings. A vote may come later.

Capital reporter Naomi Harris contributed to this article.