12.19.19 – Washington Post –

The study by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, which develops standards for new technology, found in the worst cases, Asian and African American people were up to 100 times more likely to be misidentified than white men. American Indians were most likely to be misidentified.

The faces of African American women were falsely identified more often in the kinds of searches used by police investigators where an image is compared to thousands or millions of others in hopes of identifying a suspect.

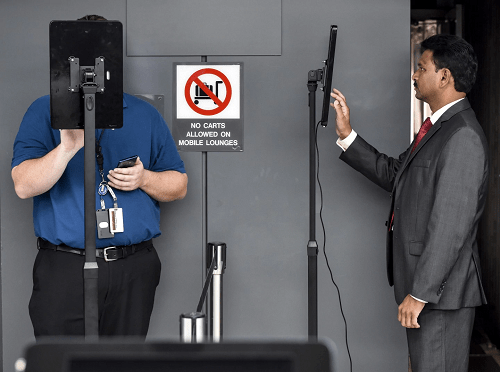

Algorithms developed in the United States also showed high error rates for “one-to-one” searches of Asians, African Americans, Native Americans and Pacific Islanders. Such searches are critical to functions including cellphone sign-ons and airport boarding schemes, and errors could make it easier for impostors to gain access to those systems.

Women were more likely to be falsely identified than men, and the elderly and children were more likely to be misidentified than those in other age groups, the study found. Middle-aged white men generally benefited from the highest accuracy rates.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology, the federal laboratory known as NIST that develops standards for new technology, found “empirical evidence” that most of the facial-recognition algorithms exhibit “demographic differentials” that can worsen their accuracy based on a person’s age, gender or race.

Lawmakers on Thursday said they were alarmed by the “shocking results” and called on the Trump administration to reassess its plans to expand facial recognition use inside the country and along its borders. Rep. Bennie G. Thompson (D-Miss.), chairman of the Committee on Homeland Security, said the report shows “facial recognition systems are even more unreliable and racially biased than we feared.”

The federal report confirms previous studies from researchers who found similarly staggering error rates. Companies such as Amazon had criticized those studies, saying they reviewed outdated algorithms or used the systems improperly.

“Differential performance with a factor of up to 100?!?” she wrote The Washington Post in an email Thursday. The study, she added, is “a sobering reminder that facial recognition technology has consequential technical limitations alongside posing threats to civil rights and liberties.”

Jay Stanley, a senior policy analyst at the American Civil Liberties Union, which sued federal agencies earlier this year for records related to how they use the technology, said the research showed why government leaders should immediately halt its use.

“One false match can lead to missed flights, lengthy interrogations, tense police encounters, false arrests, or worse,” he said. “But the technology’s flaws are only one concern. Face recognition technology — accurate or not — can enable undetectable, persistent, and suspicionless surveillance on an unprecedented scale.”

NIST said Amazon did not submit its algorithm for testing. The company did not immediately offer comment but has said previously that its cloud-based service cannot be easily examined by NIST’s test. Amazon founder and chief executive Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post.

Grother, the NIST lead researcher, said other companies with cloud-based systems had been able to submit their algorithms, including Microsoft, who he said “sent us very capable and very reliable software.” Of Amazon, he added: “Our test remains open if they elect to participate.”

The test studied both how algorithms work on “one-to-one” matching, used for unlocking a phone or verifying a passport, and “one-to-many” matching, used by police to scan for a suspect’s face across a vast set of driver’s license photos. Investigators tested both false negatives, in which the system fails to realize two identical faces are the same, as well as false positives, in which the system identifies two different faces as being the same — a dangerous failure for police, who could end up arresting an innocent person.

Some algorithms produced few errors, but the disparity in accuracy between different systems could be enormous. There is no national regulation or standard for facial-recognition algorithms, and local law-enforcement agencies rely on a wide range of contractors and systems with different capabilities and levels of accuracy. The algorithms themselves — with names such as “anyvision-004” and “didiglobalface-001″ — are almost entirely unknown to anyone outside the industry.

Algorithms developed in Asian countries had smaller differences in error rates between white and Asian faces, suggesting a relationship “between an algorithm’s performance and the data used to train it,” the researchers said.

“You need to know your algorithm, know your data and know your use case,” said Craig Watson, a manager at NIST. “Because that matters.”