2.5.22- NY Post

Over the last two years, crime has swept the US.

Two-thirds of America’s largest cities have seen even more homicides in 2021 than in 2020, with killings rising in New York from 468 to 485, in Chicago from 771 to 797, and in Houston from 400 to 467. More than 13 big cities — including Philadelphia, Austin, and Portland — set all-time records for homicides in 2021.

But one big city — Dallas — has bucked the national trend. From 2020 to 2021, homicides in the Lone Star metropolis have dropped from 254 to 220, and violent crime has nosedived by 12 percent since May last year.

How did Dallas do it?

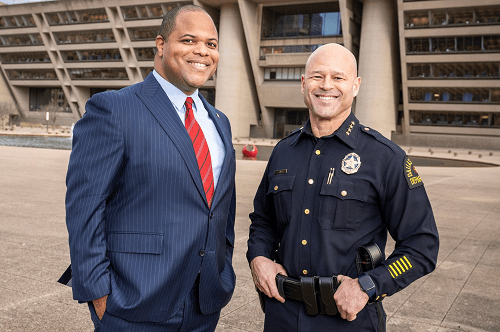

In early 2021, Dallas Mayor Eric Johnson recruited Eddie Garcia as his new police chief. Garcia, who had spent four years as the police chief of San Jose, Calif., quickly created a plan with University of Texas criminologists, implemented it, and saw crime rates drop almost immediately. Officer morale, as a result, has improved, Johnson told The Post.

“Morale is up and noticeable,” said Johnson. “The police are attacking violent crime at its source with a level of vigor and enthusiasm we hadn’t seen for years.”

As soon as he started on the job, Garcia and his team of criminologists focused on where the worst crimes happen.

‘We broke Dallas down into 104,000 grids. Just 50 of those grids are responsible for 10 percent of the violent crime in the city.’

Dallas Police Chief Eddie Garcia

“We broke Dallas down into 104,000 grids. Just 50 of those grids are responsible for 10 percent of the violent crime in the city. And so only a relatively small number of areas are responsible for a large amount of crime. It’s a small amount of individuals,” Garcia explained.

In Dallas, the most troublesome areas were apartments. “We had murders, robberies, and assaults in apartment complexes,” Garcia said.

The police, along with other city services, examined the complexes to see how they could make them safer. For each building, they would say, “It needs fencing and lighting. We ask, ‘Who do you hold accountable to get that done?’ And, ‘Do we need a park? Youth activity? Do the streets need work?’”

But their plan wasn’t just midnight basketball and conflict resolution workshops.

“Police obviously need to rid the criminal element,” stressed Garcia. He said he is seeking to balance carrots and sticks — rewards for good behavior with threats of consequences if people break laws. Focused deterrence means police made themselves more visible in violent areas, seizing 27 percent more guns and 8 percent more drugs in 2021 than in 2020.

But Dallas police do not treat all drugs equally. The department has moved away from targeting low-level marijuana possession, for example.

Prominent African-American community leader Derrick Battie, of South Oak Cliff Alumni Barricade Association, applauded Garcia’s approach to “weed out the bad elements from communities and seed in good things like sports gaming, music studios, and boxing gyms and afterschool programs.”

Garcia has also been visiting prisons with community leaders to emphasize his carrot-and-stick approach.

“In a couple of weeks I’m going to correctional facilities with violence interrupters, victim advocates, reentry services, federal partners, pastors, and voices from the community,” he said.

He said has a message for prisoners being released: “If you’re going to cause havoc, you’re going to end up back in here. But if you need job training, education, mental health, substance abuse help, we want to help you succeed.”

When I asked Garcia what explained the rise in crime in the first half of 2021 and its decline in the second half, he said, “It is morale. No plan works without officer morale. If morale is not at a certain level, there’s nothing I can do as chief to force policemen and women to make an investigative stop at 2 or 3 in the morning to take someone into custody for narcotics. They’ll only do so if they feel supported by the department and mayor.”

Echoing that sentiment is Michael Smith, a criminologist at the University of Texas, San Antonio, who worked with Garcia for three years when he was at San Jose and also helped him create his plan for Dallas.

“Morale is absolutely important,” Smith said. “We have a very sound, evidence-based plan. All components of it are based on the best science. But I’m convinced that what makes this plan successful … is the men and women of the Dallas police department who were out there doing their job assertively, not aggressively…They’re doing it assertively and professionally. They have bought into Garcia’s vision. Cops can be a cynical group but Johnson and Garcia managed to bring them on board.”

Many progressives worry that morale-boosting among officers can lead to cops getting off the hook for bad behavior.

But that hasn’t been the case in Dallas. “The use of force is down in Dallas,” said Smith. “We’ve managed to reduce violent crime in our targeted hotspots by more than 50 percent and about 15 percent citywide.”

As in many other cities across the country, activists in Dallas have called for defunding the police in recent years.

“There was a significant percentage of our activist community who wanted us to cut our police budget by 40- to 60 percent,” said Johnson. “I got protested at my house for several weeks by people saying not very nice things to me. It wasn’t fun. I had to remind myself constantly why we were doing it.”

Dallas leaders were doing it to save lives.

“Talk to someone who lives in a neighborhood racked by violent crime, drugs and the violence that comes along with those and ask if they would like to defund the police,” said Johnson, who is black and a Democrat.

“Folks in those communities never asked for, and never wanted or supported, defunding the police, or fewer police. What they’ve wanted is better trained police and a relationship with police [who] want to deter violent crime in the first place. Calls for defunding the police are coming from people who aren’t in the communities affected by the violence.”

‘Morale is up and noticeable. The police are attacking violent crime at its source with a level of vigor and enthusiasm we hadn’t seen for years.’

Dallas Mayor Eric Johnson

Battie, whose Oak Cliff neighborhood is heavily African-American and Latino, agreed. “We want to see an increase in non-police action. But we never, ever wanted to get rid of the police.”

So can Dallas offer a lesson to Democrats nationwide, who are responding defensively — once again — to accusations they are soft on crime?

“I don’t know what’s going on in other cities,” Johnson replied. “And I have no political advice for the Democrats, per se. But for people in leadership on topics of public safety, you can’t let the politics dictate what you do. You can’t chase political favor on one side or the other with solutions that don’t work — of ‘defund the police’ on one side and ‘police can do no wrong,’ and dismissing concerns of reform advocates. You can end up on either extreme easily. You have to follow the data.”

Michael Shellenberger is the author of “San Fransicko: Why Progressives Ruin Cities.”