5.25.21 – SSI

The ADT Engineering Lab in Boca Raton, Fla., tests every device that ADT installs for everything from voltage to heat to compatibility.

Two miles away from ADT’s U.S. headquarters, tucked away in a one-story building — unremarkable among dozens of others in this Boca Raton, Fla., commercial office park — is the operation colloquially known among ADTers as the “ADT Engineering Lab.” The name on its door, at suite 10, says something different.

The ADT Engineering Technology Center is one of those places most new hires at the smart home security company hear about; yet, when asked few will say they’ve ever been there. It took me two years to get my invite, the result of several months of cajoling Mark Reimer, ADT’s vice president of product engineering, into letting me come visit.

I arrived on my motorcycle and parked conveniently out front in one of the many available spaces. I’m greeted at the door by Tim Rader, senior director, product development and engineering, who dropped a casual “nice” followed by a long pause and gaze into the lot. Inside, we went straight to his office.

The whole scene looks strikingly similar to ADT’s nearby HQ building — sand-toned, fabric-covered cubicle dividers, the same bulk-purchased desks and cabinets struck in a matching khaki tone and Rader, seated behind a desk with unkempt piles of video doorbells of all makes and models, unopened boxes of sensors and security cameras, disassembled electronics whose state of composition makes it hard to discern what they started out as.

We exchange pleasantries. I know Rader, but since COVID-19 struck we haven’t been in the same office together for more than a year. Then we cut right to it, “what goes on here?” I ask

The ADT Engineering Lab was started eight years ago when Rader joined the company from Brinks (which ADT acquired at the time). Along with Rader came another lab resident, Steven Else. Between the two men are four or five decades of security industry experience.

Setting a High Bar for ADT Home Security Systems

This place, I would learn from Rader, is where ADT conducts all of its hardware certification and testing on every device it puts into a customer’s home or small business. The certification process on one product takes anywhere from a few weeks to more than a year. This work is done on products that are finished in form, provided by their manufacturers as complete and ready to go. But Rader and his team start where the device manufacturers stop, much to the frustration and occasional anger of those companies.

Skeptically, I ask, why spend months re-testing these products, which have already been tested and certified by household names — like Underwriters Laboratories (UL), Federal Communication Commission (FCC), Zigbee Alliance, Z-Wave Alliance and others?

“Our vendors hate this because of how strict we are,” Rader says. “We are uber-obsessed. I’d say 95% of the products we test have something wrong at first; 40% have some critical flaw. If we put a million devices in our customers’ homes and just a half of a percent of those fail, can you imagine the cost?,” he asks.

The bar Rader sets is admittedly high. Components going into an ADT home security system have to stand up to and guard against a lot — they have to protect the customer and protect themselves, from both the mundane (lightning strikes) and the nefarious (cyberattacks). There’s also a persistent and healthy skepticism at work: Does this thing really do what it’s supposed to?

To help answer that question, we begin walking around the lab itself, whose location was specially chosen for its many unique characteristics. Along a very long hallway, bright orange gaffing tape with faded black sharpie writing mark out distance measurements on the floor. It stretches 185 feet, so says the first mark where we’re standing. A straight line of sight stretches from the lobby to a hard-to-see steel door at the end.

“We chose this building because it’s long and narrow, perfect for conducting the range testing we need to do on our components. This hallway used to work for us, but now, with the new radios, we have to walk outside,” Rader says, as he points through the plate-glass window and across the street into another cluster of buildings.

Among the few cubicles in front is where Else and Jatin Patel sit. Else’s desk looks like Rader’s, but it has a child’s toy Ferris wheel constructed from erector-set looking pieces. An answer came to a question I didn’t ask: “He’s not playing with toys, this is to measure image warp during movement with cameras,” Rader offers.

The line between toys and tools is blurred here. Else hands me a video doorbell created by a major tech company; it’s a prototype he’s been given, one of two, so it can’t be dissected just yet. 3D printed models are laid about — roughly formed objects created for ADT executives to have and hold — the earliest samples of ADT’s future product line.

ADT Lab Conducts Unique Water Leak Testing

Rader guides me toward a tubular mess of copper and PVC piping sat upon a wooden dolly with wheels. It is a testing unit to prove if water flow sensors and automatic shutoff devices work as advertised. With pride, I’m told it cost more than $4,000 to build before the highly sensitive, German-made water flow meter was added against which devices being tested will be judged. Automatic water shutoff devices, connected to smart leak detectors, are breakthrough technology in the smart home space.

After wind and hail damage, water damage is the most frequent cause of homeowners’ insurance claims, striking 1 in 50 insured homes every year. Here in the lab is where the optimal combination of water flow accuracy and device cost is being calculated. Insurance companies are especially keen on this technology becoming mainstream, so much so they are providing steep discounts to customers with smart home systems and those with water detection devices like these.

Moving deeper into the lab we pass a spartan conference room and well-stocked snack machine. Five people regularly work in the lab, and with few visitors they’ve formed a close bond.

“We used to get together more outside of the lab before COVID,” Rader says, ruefully. “Now we get pizza once and a while, but we’re upgrading the game room. I’m bringing in the pool table from my house.”

ADT was founded nearly 150 years ago. The brand name disguises its age: American District Telegraph. Telegraphs were once a key technology and service the company provided. Today, the security tools of the trade at ADT are what you would expect from a tech company: AI, ML, LTE, video analytics, you name it. However, millions of ADT customers still rely on technology and products that were installed decades ago, and the team here must ensure those systems keep working — people’s lives depend on it.

Slideshow: Meet key players at the ADT Engineering Lab

In the room where Rader’s pool table will soon take up residence is a gaggle of computer servers, partitioned behind a glass wall in a climate-controlled chamber, and partially obscured by lead-lined curtains. The servers mimic one of ADT’s nine central monitoring stations, capable of receiving, interpreting and relaying alarm signals from myriad makes and models of control panels and radios flung far and wide across the United States in the homes and businesses of ADT’s 6 million customers.

We are also standing in the antechamber to a realistic construction of a large home environment. Walls constructed of the same composition as those found in the typical American home were erected creating these spaces to simulate how radio waves between door sensors, cameras, smart locks, light bulbs and smart plugs will communicate to a central hub or panel. If a device passes the “three-wall test” it will meet one more ADT expectation. But there’s more, and we press on.

It’s impossible to ignore the noise. Beeps, chirps and ticks are omnipresent in the ADT Engineering Lab. It’s like working among a concert of discontented smoke detectors. Clutter abounds, but it conveys a sense of creativity and genius at work.

Solving the Cellular Migration Puzzle

Charbel Hayek is a radio engineer who is responsible for certifying and testing the communications function of ADT smart home components. Today we found him on a Zoom call with a partially deconstructed CellBounce device on his desk.

Progress in cellular technology has ushered in 5G, and many U.S. cellular carriers, like AT&T and Verizon, are overhauling their networks to bring super-fast, wireless internet to their customers. Left behind are the 20-year-old 3G networks, many of which will switch off and go dark as soon as the end of this year. ADT, like all other home and small business security companies, as well as many other industries, still relies on 3G to send alarm signals from customer homes to monitoring stations.

To solve the migration puzzle, ADT developed a novel way to convert 3G signals to 4G/LTE signals with a simple in-home, plug-and-play solution, which brings us back to Hayek’s desk.

His work now is ensuring CellBounce will operate flawlessly across various geographies, systems, environments and over time. Its advantages are many, and among them are costs savings for customers and the elimination of the requirement to send a technician into many people’s homes — not trivial in today’s pandemic recovery environment.

Adorning the walls of the long hallway hang antique alarm signaling equipment alongside modern IP surveillance cameras, arranged neatly in rows on peg boards, totaling up to 30 cameras on one installation. The antiques are a novelty; the 30-camera array is to test if a system’s claimed 30-camera support can be believed. A nearby video monitor and computer prove its case.

“We joke around here that we’re all going to grow horns,” chuckles Rader, as we move on. “Why?,” I ask. “All the RF,” he responds.

Nearing the end of the long gauntlet hallway we duck into a small room with unusual-looking testing equipment set upon long folding tables. Laser-jet printed signs above each piece of equipment bear some description of each devices’ purpose and warnings. Aptly located near the rear of the building, this space can best be described as an electronic device torture chamber.

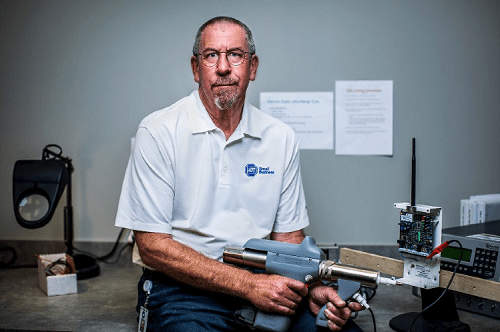

Rader begins in the middle with a tool that is at first comical in appearance — a ray-gun looking apparatus easily at home on a Star Trek movie set.

“This is our ESD,” he says, quickly elaborating that it is an electrostatic discharge gun. It has a fore grip and pistol grip, adding to its ominous appearance. “We use this to simulate the shock you might give to a panel or sensor if an install tech had been dragging his feet across your grandmother’s shag carpet,” Rader explains.

Next to the gun sits a much more innocent but far more dangerous piece of testing equipment. The lab uses a high-voltage generator, capable of producing current at 6.6KV at 300 amps, to simulate lightning strikes. When it’s in use, the operating procedure is to lock the door and always operate with two people at a time, just in case. “It’s not if you’ll die, it’s how quick,” admonishes Rader.

But, lighting strikes are becoming less of an industry problem. Most all sensors and many devices in today’s smart home are wireless or battery-powered now, eliminating a former scourge of wired home security devices and electronics. The need for the high-voltage generator may soon become as obsolete as wired door sensors.

ADT Takes Motion Detecting to New Heights

Nearing the end of my lab tour, Rader leads me into the largest room in the building. Its ceiling is high and numerous lines of painter’s tape stretch across the long wall forming angular patterns like sun beams.

“There are only two of these in the U.S.,” Rader says, proudly.

We are standing in the motion detector testing space (officially, the walk-test room) at the ADT Engineering Lab. Here, the testers walk, run and crawl pre-defined patterns, also marked by fluorescent tape on the floor, while instruments measure when motion signals are received by the sensors, mounted at ceiling level, like in a home. Testing occurs with volunteers approximating a 120-pound subject and larger 200-pound subject. And then there’s “A.S.A.P.”, the custom-built robot whose job it is to stand in for an average-sized pet.

Home security motion detectors operate by detecting changes in temperature in front of them. For example, if the ambient room (or floor) temperature is 72° and a body mass with a temperature of 95° passes into the field of measurement, an alarm will be triggered. But, with all home security apparatuses, not all are created equal, and not all live up to their promises, which is why the lab tests these sensors in many conditions.

In fact, the lab installed three blast furnaces capable of heating this space to 100° for up to three days consecutively to simulate empty homes or warehouses. Rader’s claim of being uber-obsessed raced back to back my mind.

The lab is preparing for an upgrade to introduce more automation to the testing process and to focus on newer technology. Also, a 2020 partnership with Google set in motion plans at ADT to develop a wholly new smart home platform, ushering in many new categories of smart home devices for the lab to test and refine. Other aspects will shift, too, Rader predicts.

“We’re becoming more forward thinking. We’ll be designers, and other vendors will build our products under license from ADT,” he says. “We’re moving from testing other people’s products to inventing our own solutions.”

It’s a significant shift for ADT; the country’s largest integrator of smart home security systems is evolving into a smart home innovator. Ambient computing is on the horizon, and Rader lights up with excitement when talking about the technology’s promises.

There’s good reason to believe many new inventions will come from the ADT Engineering Lab; inventions that will make people’s lives safe and simple, at home, work and on the go. And, they will add to the 18 combined patents the team has already been awarded with more on the way.

Paul Wiseman is the corporate and marketing communications manager at ADT. This article first appeared on SSI sister site CEPro.