5.24.21 – Clarion Ledger

Can new funds transform Mississippi’s digital desert into a broadband mecca? Llewellyn Jones. Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting.

Mississippi could see more than $700 million in federal funding for broadband over the next few years, thanks to the CARES Act, FCC grants and a possible infrastructure bill.

That doesn’t include indirect funding sources such as PPP loans for broadband-related businesses, subsidies for ratepayers, grants for 5G development and older grant opportunities like the FCC’s Connect America Fund.

The large influx of investment is likely to dramatically alter the digital landscape of Mississippi, which has long been a broadband desert, ranking last in the nation for internet connectivity. According to U.S. Census data, Mississippi has the lowest rate of broadband subscribers per capita.

With the large investment has come a debate as to who gets the funds and where the money will go. Sometimes the grants are divvied up through the FCC’s broadband auctions, which Roberto Gallardo, director at the Purdue Center for Regional Development, called a “race to the bottom” because of how they reward the lowest bidder.

Mississippi’s U.S. Sen. Roger Wicker, who has been influential in federal funding for broadband, stated that, while the investment will be “transformative,” there is an ongoing need to ensure the buildout delivers broadband to the underserved communities as promised.

The Biden infrastructure bill, the American Jobs Plan, has yet to pass and faces stiff opposition, but it would include an additional $166 million for Mississippi broadband.

Wicker has been critical of the Biden bill, and instead supports a separate infrastructure initiative that would provide tools for local communities to fund broadband and other developments. The total funding for broadband in that package would be $65 billion.

Broadband in rural areas has long been a large contributor to the digital divide — the gap between who benefits from reliable internet connections and who doesn’t.

As the pandemic pushed schools into online learning, many school districts and colleges were faced with the struggle of ensuring everybody had access. For some, this meant mailing out mobile wifi hotspots to students, opening school parking lots for wifi access, or even sending out homework by mail.

Large swaths of the country might be eager and willing to pay for faster cable service, but there are large upfront costs to run fiber optic cable to those communities. Without enough potential subscribers, Internet service providers have been unwilling to invest. The more rural the location, the larger those upfront costs can be and the fewer subscribers available

At one time, households that could connect to a DSL line were considered broadband. But in the current age where streaming video is necessary for telework, telehealth and education, DSL is not considered broadband anymore.

The Broadband Enabling Act and electric cooperatives

It’s not just the loosening of the purse strings at the federal level, but also changes at the state level that have made a difference.

The 2019 Broadband Enabling Act passed in the Mississippi Legislature allowed electric cooperatives to provide broadband for the first time, and other state bills directed CARES Act money to broadband development.

Cooperatives appear to be well-positioned to provide connections as they already have infrastructure in place. They own the rights-of-way to run fiber to neighborhoods, which keeps development costs down substantially. As electric utilities, they already are required to provide a certain level of customer service and are overseen by the Mississippi Public Service Commission.

As opposed to commercial utilities, electric co-ops are nonprofits owned by their members, who are also their customers. Mississippi has 26 member-owned electric power associations that distribute power to more than 1.8 million Mississippians.

According to Chris Mitchell, director of the community broadband networks initiative with the Institute for Local Self-Reliance in Minneapolis, co-ops are structured to be responsive to those that depend on their services, not unlike municipal broadband providers. All their customers get a vote for the board, which hires a manager that is ultimately responsible for what the co-op does.

They are also more often focused on the communities they serve.

“AT&T is trying to figure out where to invest across the world to get the best return for its shareholders, so it puts little into Mississippi,” Mitchell said. “But the co-ops in Mississippi aren’t about to start investing in a network in Dallas. They are focused on what is best for the region they are part of.

AT&T is the largest broadband provider in the state, and between 2017 and 2019 the company invested nearly $750 million in its wireless and wireline networks in Mississippi to expand coverage and improve connectivity.

Following the federal investment in broadband, state co-ops are set to lead the state’s digital makeover. Of the federal funds destined for broadband, the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund is the largest pot of gold.

Members of the Rural Electric Cooperative Consortium won 45% of the fund’s auctions in Mississippi and a number of them received PPP loans and CARES Act grants as well. Nationwide, they won over $1.1 billion in grants from the FCC auctions.

5G wireless technology project: C Spire announces $1 billion investment in Mississippi

Rural Digital Opportunity Fund and reverse auctions

While the fund’s money is the largest federal broadband investment, it may also be the most contentious.

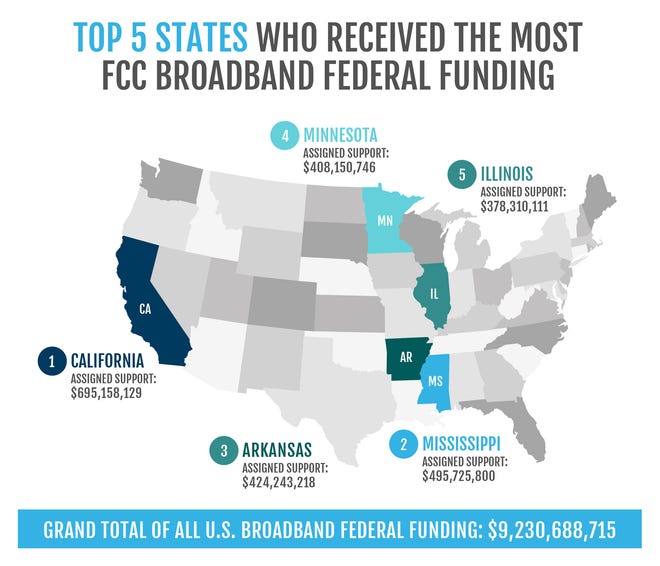

Almost $495 million from the fund is destined for Mississippi, second only to California. Despite winning a large percentage of its funding in Mississippi and nationwide, the co-ops have been highly critical about how the FCC handles the auctions, where contractors bid on grant money.

According to Stephen Bell with the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, the co-ops’ concern lies with who was allowed to bid on and win the auctions, such as fixed wireless providers.

With fixed wireless, providers send a wireless signal to customer’s homes from a fixed location rather than running cable or fiber to a home. While fixed wireless providers can provide fast, affordable service in rural and other locations, it is highly contingent on the surrounding landscape. Service can be interrupted by buildings, terrain and distance.

According to Gallardo, fixed wireless companies bid in the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund offering gigabit speeds that they may not be able to provide.

“Maybe they can offer it here and there, between towers and some users or between connection points, but not entire neighborhoods,” he said.

The co-ops also have been critical of low-orbit satellite providers like Elon Musk’s Starlink. Regular satellite internet connections can provide internet service in far-off rural locations with no need for fixed wire, but they have issues with latency and usually provide no ability to upload data. This means customers need to have an alternate connection like dial-up or DSL to send email or upload content.

Starlink improves upon that with fast upload capability and faster download speeds akin to a fiber connection accessible from anywhere. The company was the second-largest winner in the Rural Digital Opportunity Funds auctions in Mississippi, next to the co-ops. But the co-ops accused the technology of being “unproven.”

Starlink filings with the FCC state the technology is not experimental and that it provides service to over 10,000 customers nationwide with no speed or latency issues.

In Gallardo’s view, there is ample room for fixed wireless, Starlink and the co-ops to win in these auctions, but the problem lies with how the auctions reward the lowest bidder and not necessarily the best option.

The FCC has a system that attempts to weigh bidders by the speeds they offer and other factors, but auctions are sometimes won by bidders unable to provide their advertised speeds or complete development by their stipulated deadlines.

The FCC can rescind auction results. Entrants first bid following the submission of a short-form detail of their capabilities. Following the auction, they must file a long-form document detailing their prospective engineering approach, which all need to be approved by the agency.

To Gallardo, more needs to be done upfront before the auction occurs to better weigh what is needed for each community.

“They need to gather local input and crosscheck it with federal data, which is currently not good,” he said. “A homeowner’s association can tell you things that a speed test can’t. They know DSL is terrible when, come Friday evening, it’s slow as molasses.”

Thanks to COVID-19 cash:Faster internet is coming for parts of rural Mississippi

FCC broad maps a point of contention

Another point of contention has been the FCC’s woefully vague broadband maps. These are maps that designate which Census blocks have broadband capability and which don’t.

The maps have been regularly criticized for being misleading because of their reliance on self-reported data from internet service providers and their lack of granularity.

The map relies on Census blocks that can vary in size from small city blocks to large county-spanning tracts. Because of their size, those larger rural tracts can encompass a majority of households without broadband access. Yet as long as one household has broadband, the FCC map will show the entire Census block having broadband.

Upgrading the maps has been on the FCC’s radar for some time, and acting chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel announced a broadband data task force in February to resolve the issue with more precise information.

With most of the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund auctions already completed, the upgrade may be too late to help target funds, but it may come in time for any investment that would come out of the infrastructure bill.

Nationwide:1.7 million rural Americans may get broadband after FCC auction

Sign-up rates and affordability

Considering Mississippi’s current lack of connectivity, the influx of investment is expected to be a sea of change for the state, but it’s hard to say by how much.

There’s no guarantee that Mississippians will sign up en force once the option becomes available, although nationwide trends show adoption rates increase substantially as broadband becomes available.

Cost and household income, whether urban or rural, are the largest factors in broadband adoption. Not just in rural areas, urban areas can also have large swaths with few broadband connections, according to data in a 2017 report by the Brookings Institution.

The FCC’s Emergency Broadband Benefit program has a pool of money available to help households subsidize the costs, but there may be a need for more.

According to Anna Read with The Pew Charitable Trust’s Broadband Access Initiative, states like Tennessee have grant programs that set aside funds specifically for digital literacy to buffer the success of their broadband infrastructure programs.

Subsidizing ratepayers, rather than subsidizing the providers, could also be a better way to solve some of the debates coming out of the auctions.

According to Doug Brake, director of broadband and spectrum policy for the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, providing vouchers for residents that are otherwise unconnected could help lower prices without distorting the market and unfairly subsidizing one competitor over another.

This story was produced by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization.

Email Llewellyn Jones at llewellyn.h.jones@gmail.com.