Governing – Ransomware attacks are becoming more sophisticated and taking longer for governments to recover from. Some of Baltimore’s services have been down for nearly a month. NCSL resources on 2019 cybersecurity legislation.

SPEED READ:

- Baltimore suffered a ransomware attack nearly a month ago and has yet to restore critical networks.

- The city refuses to pay the hackers and is asking the federal government for financial aid.

- Ransomware attacks on governments are on the rise — and becoming more sophisticated.

Cyberattacks on local governments are on the rise — and they’re becoming more sophisticated. The latest case in Baltimore, where the city is still struggling to restore critical networks more than three weeks after being hacked, could be a harbinger of things to come.

Already this year, at least 24 municipalities have reported ransomware attacks, including Amarillo, Texas; Augusta, Maine; Imperial County, Calif.; Garfield County, Utah; Greenville, N.C.; and Albany, N.Y. That’s on pace to surpass last year’s total of 53, according to data collected by the tech company Recorded Future.

“As city governments become more sophisticated themselves and rely more on AI [artificial intelligence] machine learning … that creates more vulnerabilities in the network,” says Carl Ghattas, a former executive assistant director for the FBI’s national security branch and now an executive director for Ernst & Young’s government consulting practice. “Combined with the fact that actors are becoming more sophisticated themselves, these types of attacks are likely to continue if not increase.”

Ransomware attacks, in which hackers take systems hostage and demand a ransom, began around 2013 when cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin provided a secure and untraceable way of collecting the money. Since then,169 ransomware incidents have affected state and local governments, according to Recorded Future.

Meanwhile, hackers are starting to shift away from phishing scams that rely on a city employee to open an email and click on a link or document that gives hackers access to a system. Instead, they’re gaining direct access to governments’ systems through password-generating software.

In Baltimore, hackers exploited a cybersecurity tool developed by the National Security Agency. They paralyzed part of the city’s computer network, causing delays in home sales, online payments and other major services. Hordes of experts in the federal and private sector are working on restoring the network with no end in sight. The city is taking the somewhat unusual step of asking the federal government for financial help to cover the cost.

Ransomware demands are typically small — anywhere from a few thousand to tens of thousands of dollars. Baltimore, however, is being held hostage for 13 Bitcoin, or about $100,000. But governments generally don’t pay them so as not to encourage more attacks.

The Length of Recovery

The lasting impact of cyberattacks varies depending on their scale and a government’s preparedness.

Some cases are minor: When the St. Louis Public Library was hacked in 2017, the library had backups for the encrypted files and refused to pay the ransom.

But in Bingham County, Idaho, a ransomware attack that same year brought down the county’s website and disrupted 911 calls and emergency dispatch communications. Officials worked for weeks to rebuild the county’s computer infrastructure and avoid paying the $28,000 ransom. In the end, they paid a $3,500 ransom after determining that would be cheaper than buying new servers.

One of the most devastating attacks was last year in Atlanta. The hack disrupted Wi-Fi service at Hartsfield-Jackson Airport, the world’s busiest air traffic hub, for more than a week and halted online payments to the city for weeks. It took months for Atlanta to fully restore its systems.

While most agree that governments can’t create a foolproof defense against cyberattacks, there are certain things that help in the aftermath. Step one, says Ghattas, is having a response plan to minimize disruption to services and protect data.

“Recovery often takes longer when there is not a tight cohesive strategy in place to deal with a cyberattack,” he says.

Cyber insurance also helps ease concerns about paying for the response. In Baltimore’s case, it didn’t have cyber insurance — even though it was hit by a ransomware attack last year that affected city phone systems. That’s not good for the city’s credit, says a Moody’s Investors Service report.

“[The] city’s lack of investment in cybersecurity — when it had already fallen victim to a similar attack — will likely result in significant out-of-pocket expenses,” wrote analyst Nisha Rajan.

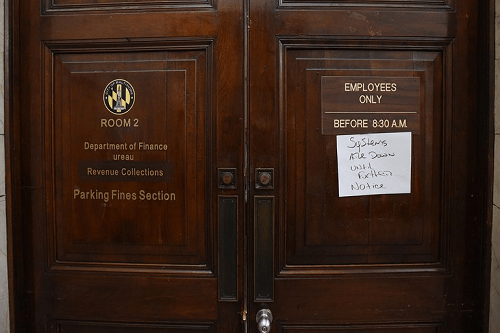

For now, Baltimore is experimenting with manual workarounds for transactions typically done electronically. The city has declined to say how long it will take for services to return to normal.

Even when a government does everything right, it can take months for a full recovery. In a separate report, Moody’s highlighted Alaska’s Mat-Su Borough, a community of 104,166 people just north of Anchorage, which suffered a ransomware attack in July 2018. It wasn’t until February of this year that the system was essentially restored.

Luckily, the impact on residents was minimal. Moody’s applauded the borough’s “rapid and coordinated response that involved protecting as much information as possible, maximizing transparency with residents to minimize reputational damage, and maintaining essential services and revenue collection.”

The community also had cyber insurance, which helped curb financial losses.