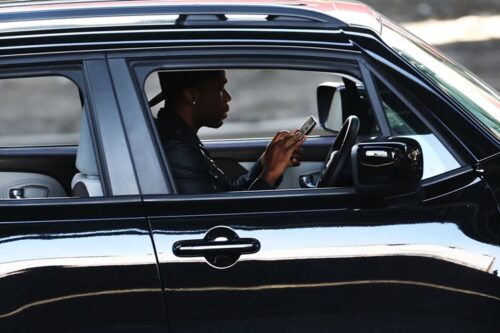

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

2.22.24 – VOX

During the pandemic, distracted driving increased, and it hasn’t gone down since. American drivers use their phones while behind the wheel more often than Europeans, according to data gathered by a contractor for insurance companies, which helps explain the growing disparity in traffic deaths between the U.S. and Europe.

Marin Cogan is a senior correspondent at Vox. She writes features on a wide range of subjects, including traffic safety, gun violence, and the legal system. Prior to Vox, she worked as a writer for New York magazine, GQ, ESPN the Magazine, and other publications.

Until relatively recently, good data on the problem of distracted driving has been hard to find. The government estimates that 3,522 people died because of it in 2021, but experts say the official number probably majorly undercounts the number of deaths, in part because police are rarely able to definitively prove that a driver was distracted right before a crash.

In the last few years, though, the data on distracted driving has gotten better. Cambridge Mobile Telematics is a company that partners with major insurance companies to offer downloadable apps that drivers can use to save money on their rates. Via the apps, Cambridge Mobile Telematics (CMT) uses mobile phone sensors to measure driving behavior, including whether a person is speeding, holding their phone, or interacting with an unlocked screen while driving (the company says it doesn’t collect information on what the drivers are doing on their phones). Its work gives the company insight into the driving behaviors of more than 10 million people.

CMT recently analyzed driver behavior during millions of car trips. What it found should be troubling to anyone who uses a road in the US: During the pandemic, American drivers got even more distracted by their phones while driving. The amount of distracted driving hasn’t receded, even as life has mostly stabilized.

The company found that both phone motion and screen interaction while driving went up roughly 20 percent between 2020-2022. “By almost every metric CMT measures, distracted driving is more present than ever on US roadways. Drivers are spending more time using their phones while driving and doing it on more trips. Drivers interacted with their phones on nearly 58% of trips in 2022,” a recent report by the company concludes. More than a third of that phone motion distraction happens at over 50 mph.

We’re also spending nearly three times more time distracted by our phones than drivers in the United Kingdom and several other European countries. US drivers spent an average of 2 minutes 11 seconds on their phones per hour while driving, compared to 44 seconds per hour for UK drivers, CMT found. The company compared the driving behaviors of US and European drivers because road fatalities in the United States surged during the pandemic and European fatalities did not. In 2020, 38,824 people died on US roads. In 2021, that number rose to 42,915 people, and the highest number of pedestrians were killed in 40 years. In 2022, the overall deaths stayed high, around 42,795, among them 7,508 pedestrians.

The United States is increasingly an outlier when it comes to traffic fatalities, with rates 50 percent higher than its peers. The CMT findings suggest that the way Americans use their phones while driving could be one important reason why, along with road and vehicle design and a lack of consistent traffic safety enforcement.

“The way individuals are driving their vehicles in the US is distinct from the way they’re driving in Europe,” says Ryan McMahon, senior vice president of strategy for Cambridge Mobile Telematics. That extra time Americans are spending on their phones while driving increases risk: In more than a third of crashes the company analyzed, McMahon says, the driver had their phone in their hand a minute prior to collision.

The large increase in risky driving behaviors in the US started basically as soon as the pandemic began. “We saw this incredible increase in distracted driving. You could almost track it by the day schools started to shut down,” McMahon says. “When mobility changed, risk increased dramatically.”

The individual and collective consequences of our cellphone compulsions are stark: The most distracted drivers are over 240 percent more likely to crash than the safest drivers, according to the report.

The report also notes how the rise of smartphone use roughly corresponds to the rise in pedestrian fatalities: About 4,600 people were killed while walking in 2007, the year the iPhone was introduced. By 2021, with 85 percent of Americans owning smartphones, the number rose to 7,485.

Why American drivers got more distracted during the pandemic

McMahon and other experts on distracted driving have some theories. Culture may play a role: The shift to working from home, the fact that Americans work longer hours and vacation less, and the expectation that they need to be available to their colleagues even while driving is a notion many Europeans would scoff at. (As someone currently living in Europe after a lifetime in the United States, my highly subjective observation is that people really do seem less work-crazed in Europe. And while phone-checking while driving definitely happens, I see it a lot less than I do in the US.)

“I do think this notion of work in our country, and [the idea that] you have to be available 24-7 has also exacerbated it,” says Pam Shadel Fischer, a senior director at the Governors Highway Safety Association, who’s been working for decades to reduce risky and impaired driving. “It’s absolutely a cultural issue.”

The most compelling theories, though, are structural and psychological. In the United States, infrastructure is built around cars, and Americans generally have fewer public transportation options than Europeans do. They spend more time in their cars, commuting, doing chores, and taking children to school than people in European countries, and they are far more likely to make these daily trips on roads that are straight, flat, and built for easy car travel: a perfect recipe for boredom.

While it’s difficult to generalize too much about Europe, anyone who’s lived or visited there can attest to the differences inherent in roads built before the age of the auto, where pedestrians are considered important road users. The road design, the topography, and the presence of people on foot demand drivers’ attention. “You see more distraction happening when people are more familiar with roads,” McMahon says.

The type of car also may matter a lot. In the US, the CMT analysis notes, 94 percent of car drivers said they were driving cars with automatic transmissions. Only 33 percent of UK drivers answered the same. Manual shifting requires more active engagement with the vehicle.

It’s also possible that Americans are getting more comfortable with risk precisely because their vehicles keep getting safer for the people driving them (if not for people outside of them). “We’ve got all these safety features,” Shadel Fischer says. They convince drivers that “‘everything is fine! The car will take care of me, no big deal.’ They overestimate what those safety features are designed to do.”

Another challenge is that there are frequently no negative consequences for using your phone while driving. It’s easy for people to do because they’ve done it before with no problem — until it causes a crash.

What could make drivers put down their phones?

A tech industry giant genuinely interested in improving lives and mitigating the harm and disruption caused by its products could find a way to disable distracting devices, leaving them available only for, say, GPS and emergency calls. “I’m convinced that the solution is the technology,” Shadel Fischer says. “We shouldn’t have to do anything.”

Apple introduced a feature to the iPhone in 2017 that automatically puts the phone in “do not disturb” mode while driving, but it’s extremely easy to turn off. So we are left mostly with interventions into individual behavior.

On the policy front, activists like Jennifer Smith, whose mother was killed in Oklahoma in 2008 by a driver talking on his cellphone, have been working with states to pass laws to end distracted driving. Forty-four states have some sort of distracted driving laws on the books, and 27 states have bans on hand-held cellphone use.

In the distracted driving report, Cambridge Mobile Telematics looked at how driver behavior changed after a state passed a “hands-free” law and found that it led to a 13 percent reduction in phone motion while driving in the first three months after a law took effect. But those changes tended to diminish over time, and there’s wide variation among the states both in terms of public awareness of the laws and traffic enforcement, which declined in some states during the pandemic. Without high public awareness or enforcement — which is difficult to do well because it relies on law enforcement officers witnessing the distracted driving and enforcing the laws equitably — getting good compliance can be difficult.

That’s why policymakers are taking a multi-pronged approach to the issue, trying to find ways to educate the public and make the laws enforceable. “It will take a long, sustained effort to change driver behavior if we want to have fewer deaths in this country,” says Michelle May, manager of the Highway Safety Program at Ohio’s Department of Transportation.

Ohio’s “hands-free” law went into effect last year; since then, May says, the state has used telematics data and tracked an 8.1 percent decline in driver distractions. But May expects the effort to reduce phone use while driving will be a long-term effort, akin to the effort to reduce drunk driving and getting people to wear seatbelts.

Financial incentives can also help. Car insurance rates have skyrocketed in recent years, becoming a leading cause of inflation and contributing to the financial burdens associated with car ownership, which disproportionately affects low-income and working-class Americans. The use of telematics-based apps by insurance companies offers drivers an opportunity to save money on their insurance rates. Research into the use of the apps suggests that drivers who regularly receive feedback on their driving habits tend to use their phones less while driving. The data can also help state departments of transportation better locate areas with more distracted driving, which could in turn help influence road design. “We’ve found that simple things like using paint to narrow the lanes gives people the illusion that they’ve got to slow down,” Shadel Fischer says. “The road design does play a role in how we act.”

In other words, there are ways to address the problem but they rely heavily on a bunch of solutions working with one another, at a time when our road safety system appears to be breaking down. “Every single piece has to work in concert with the other or it won’t be successful because we’re up against such a huge scale of a behavioral problem,” Smith says.

The stakes couldn’t be higher, though, and getting this right will undoubtedly take some combination of policy intervention, industry investment, and a willingness among drivers to put their phones down and pay attention.

Until then, the status quo is an advanced country with incredibly high rates of road death, where, over time, almost everyone will know someone who lost their life in a car crash. “Somehow, we’re just accepting 42-45,000 people in the US dying in this manner every year,” McMahon says. “It’s preventable.”