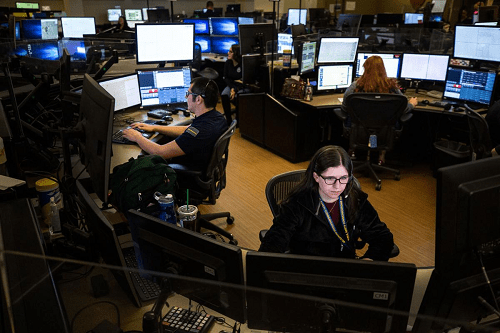

Tucson is the second U.S. city to standardize questions police operators ask 911 callers, which helps give officers more consistent details. Josh Galemore / Arizona Daily Star

12.2.19 – Tucson.com – By Stephanie Casanova Arizona Daily Star

Since Tucson combined its police and fire communications centers in 2018, hold times for 911 calls to police have been cut by three-fourths.

The city has also upgraded its technology to dispatch multiple fire units from different stations to multiple calls at the same time, which is expected to reduce response times.

Another change makes Tucson the second U.S. city to standardize questions police operators ask 911 callers, providing officers with more consistent information during emergencies.

“People should have greater confidence the response times are going to be better, have greater confidence that the wait times when they call 911 are going to be reduced,” Kozachik said. “There is not a downside in terms of customer service on this.”

CONSOLIDATION, CROSS-TRAINING REDUCE WAITS

In December 2017, the Tucson mayor and council adopted a plan for consolidation, moving police and fire communications under a new public safety communications department.

The city manager’s concept is “one city, one team,” said Angel Spencer, public safety communications administrator.

In the first 18 months since the consolidation, hold times for 911 calls for police have been reduced on average by 76%, said Chris Conger, interim deputy director of public safety communications.

That 76% translates to hold times going from 60 seconds to 14 seconds, Conger said. Spencer credits some of that reduction to staff additions and the training of call takers to have a broader skill set.

Fire calls have historically been low and have stayed low since the departments combined communications, Conger said.

Communications specialists are now trained to serve as operators for fire, including emergency medical services, and for police. Before consolidation, a 911 caller would tell the initial operator their emergency and would then be transferred to either the Police or Fire Department, where they would have to repeat some of the information they had provided to a different operator.

“That cross-trained person is not going to transfer that call,” Spencer said. “They’re going to be able to ask what you need and they’re going to be able to handle it right then and there.”

The city created new job classifications in the center: public safety communications specialists tiers I, II and III.

In 2017, 911 operators made $12.17 an hour and police operators made $14.10 an hour. Fire dispatchers started at $15.32 per hour while police dispatchers made $19.24 per hour.

By combining functions and giving employees more training and more skills, city officials realized they had to raise the pay rate, Conger said.

Tier I specialists make $17.50 an hour and Tier II specialists make $19.20 an hour. A pay rate for Tier III specialists has not been set, Spencer said.

In 2017, there were roughly 160 employees between the two communications departments.

Since consolidating, the communications center has continued hiring, Spencer said.

The center operates ideally with 163 specialists. Currently, it has 147 employees, with 61 people hired in 2018 and 33 in 2019 so far.

The center will start another hiring process at the end of this year, Spencer said.

Spencer and Conger could not provide specific amounts the city has saved since consolidating, but Spencer said there have been reductions to technology costs. The city now pays one bill for any upgrades and maintenance costs for software systems like the 911 system and the recording system, among many others, Spencer said. Those costs were duplicated before the consolidation.

TUCSON FIRE GETS NEW DISPATCH SYSTEM

The Fire Department started using a computerized dispatch system last month that allows dispatchers to focus on tracking units and ensuring the closest unit is responding to each call, Conger said. It also helps mobilize fire units faster.

On busy days for firefighters, like during a big monsoon, the new system’s ability to dispatch multiple calls at once will help units respond faster, Conger said.

The computerized system is expected to provide efficiency and cut response times, Spencer said, though it’s too soon to study the effects.

The system has also come with changes in technology at fire stations, which the firefighters appreciate, said Capt. Joshua Housman, a spokesman for the Tucson Fire Department.

There’s a new alarm system that the firefighters call the heart saver. Instead of waking up instantly to a loud alarm and a bright white light, firefighters now wake up to a more gentle sound and a gentle red light, Housman said.

He said studies are showing it’s healthier for someone to wake up gradually than instantly, increasing their heart rate from 60 beats per minute to 120 beats per minute. Firefighters still wake up and get out the door in the same amount of time as they used to, he said, but they get a couple of extra seconds to wake up.

Fire stations also upgraded to monitors where they can see addresses marked on a map that appears once they’re dispatched. In the past, the driver would have to look at a map on the wall, Housman said.

Because fire units are dispatched from a set location, whereas police are dispatched from the field, the system is only used for fire calls.

Using a computerized fire dispatch system has not reduced jobs at the communications center, Conger said.

STANDARDIZED QUESTIONS PROVIDE CONSISTENCY FOR POLICE

The communications center has also started using a criteria-based dispatch system for police that standardizes the questions operators ask callers when gathering information, Spencer said.

Operators have used the system for fire and EMS calls since 2017, but Tucson is the second city in the U.S., after Washington, D.C., to implement it on the police side, Spencer said.

Operators use a computer program to identify whether the call is for a medical, police or fire emergency. Under each topic is a list of questions the operator needs to ask.

They then click from a menu of events identifying the nature of the call, bringing up more questions the operator needs to ask.

“Anything in red is something that we absolutely have to ask for that call type,” said Diane Gustus, a Tier II specialist. “We want to make sure that we’re getting that information because that will help determine the response.”

The questions have always been a part of training. But they were taught as part of a general understanding of what information operators had to get, as opposed to being a standardized system operators always have available to look to during a call.

“Oftentimes it’s really, really busy and we’re expecting our personnel to go from call to call to call and be as efficient but as effective and qualitative as possible,” Spencer said. “We introduced this so that we can assist them with that.”

Shayl McCormick, a public safety communications coordinator and an instructor for criteria-based dispatch, said the new system helps operators especially when they’re still training or when they’re especially busy and need to remember specifics.

“We can’t be vague on the police side,” she said. “We have to be very specific in our needs so that we get exactly what we want.”