9.8.22 – ABC13 — HOUSTON, Texas (KTRK)

The agency in charge of making sure every school district across Texas submits school safety plans, including what to do in an active-shooter situation, is “too lenient” and failed to follow-up with hundreds of districts who did not submit their plans on how to keep students safe at school, according to state lawmakers.

13 Investigates found the law that calls for every district to create a safety plan also makes nearly everything about them confidential so the public doesn’t know which districts have one and which ones don’t.

“When we ask school districts around the state to prepare and plan and submit an active-shooter response plan and other hazard mitigation plans, we expect accountability there. We expect that those goals will be accomplished and each district will perform,” Sen. Brandon Creighton, R- Conroe, told 13 Investigates’ Ted Oberg. “We found through those audits over the past year and a half that some districts were late in submitting those active shooter response plans and those other hazard response plans.”

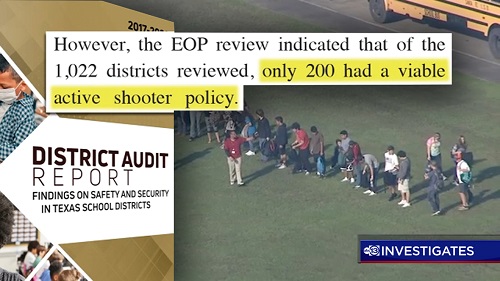

All 1,022 Texas public school districts are required by law to create multi-hazard emergency operations plans (EOP) and active shooter plans and submit them to the Texas School Safety Center.

But a 2017-2020 audit of those plans found only 67 districts – or 7% of all districts – “had an EOP that was deemed sufficient, meaning it met the common or best practices necessary to be a viable EOP.” The audit also found just 200 districts had a “viable active shooter police.”

With the current school year underway, Texans still do not know how many school districts have viable plans or which school district’s plans are insufficient.

When pressed by state lawmakers during a Senate hearing for the Committee to Protect All Texas this summer, Texas School Safety Center Executive Director Kathy Martinez-Prather said every school district has submitted a basic plan, but could not answer questions about how many of those plans are “high quality” and have a passing grade.

“We are not charged with doing follow-up compliance checks,” Martinez-Prather said during the hearing.

Sen. Royce West, D-Dallas, responded, “Wow. Who is? Do you know?”

Martinez-Prather said, “I don’t think anybody is.”

When Sen. Larry Taylor, R-Friendswood, asked her “how many school districts are failing right now” and “where are we today,” Martinez-Prather referred back to the initial audit from 2017-2020.

Taylor said that was unacceptable.

“This is two years. I’m sorry, I don’t want to hear about another six months to bring them to compliance. We’re two years into this. We’ve already had the initial assessment. They failed miserably. I think I can say that safely based on the numbers you said that we only had a handful even close. Where are we today?” Taylor asked.

Martinez-Prather ultimately said after years of working with schools, every district has submitted a basic plan, but she doesn’t know how many of them would be considered high-quality plans.

“Is there room for improvement? Absolutely,” she said.

13 Investigates wanted to know which districts are following the law by creating and submitting a sufficient plan, and which ones aren’t.

“The one thing that (you) can’t ask is to have that plan put on the internet for everyone to read because you don’t want a potential school shooter reading the emergency operations plan,” Sen. Paul Bettencourt, R-Houston, said. “But you have to demand that they’ve got the plan. You have to demand that there’s been training to the plan, and you have to make sure that there’s a demonstrative commitment to the plan to maintain it, because part of the problem is you can get a plan started and then it goes to dust because people never take it out of the closet.”

Our team didn’t ask for a copy of the plans – just for a list of schools who failed the audit, but the Texas School Safety Center who collects them is refusing to release that information.

Still, our 13 Investigates found there’s little accountability for districts who don’t submit a plan on time. By law, if a school district doesn’t submit a plan, they must hold a public hearing notifying the public. But, despite hundreds of districts failing to submit a plan during the 2017-2020 audit cycle, just one public hearing was held.

“If only one public hearing is being held, even though 200 districts only submitted a sufficient, comprehensive hazard response plan, including the active shooter response, they’re way behind,” Creighton said.

In her testimony this summer, Martinez-Prather said the Center just calls on districts to conduct self-reported audits and that it does not go out and do the audits for them.

“It’s a desk audit. We’re making sure that when we look at an active threat plan, that their plan isn’t just to call 911 and go into lockdown. Now that might be part of the response, but what we’re looking for is making sure that what are you doing to prevent and mitigate this from happening. What policies and procedures do you have in place,” she said. “The challenge we have is we’re not on that campus every single day.”

Creighton said he expects during this upcoming legislative session in January, there will be a number of bills submitted by lawmakers to improve school safety and ensure every district has quality plans in place.

“I believe the school safety center should be either enhanced to have more teeth, more personnel and more accountability from an auditing process on the ground at each school district, rather than just an honor system situation that is currently the case with school districts maybe sending in an active shooter response and hazard mitigation plan and maybe not,” Creighton said. “We are past that day and the state, I believe, in my opinion, as one senator in the Capitol, that we will make some significant changes there.”

Although school districts are expected to continuously be reviewing their emergency operations plans, they’re only required to report them to the center every three years.

Bettencourt also expects that to change this legislative session.

“They’re going to have to be renewed at least once a year. We just can’t operate the same way,” he said. “You can’t prop the doors open anymore. You can’t keep a door that’s clearly designed to be locked on purpose, to keep external people from coming in, much less a shooter — that just can’t be the culture anymore because no matter what happens with any other debate, Washington, Texas, anywhere in the country, if you can’t lock that school perimeter, then there’s going be tragedy after tragedy after tragedy.”

He said lawmakers are committed to making sure districts who do not provide their school safety plans on time are held accountable.

“What’s at risk is students and teachers dying that shouldn’t have died. That’s what’s at risk. That’s why this is important and I don’t think my colleagues and I are going to stop until we get the right answers to the school safety side of this,” he said. “At this point in time, if a board of trustees sits on that emergency operation plan, that response plan that they’re supposed to do, there will be zero tolerance.”

$100 million in school safety funding

In 2019, following the Santa Fe school shooting that killed 10 students and teachers in 2018, Texas lawmakers approved nearly $1 billion for schools to invest in “exterior doors with push bars, metal detectors at school entrances, erected vehicle barriers, security systems to monitor and record school entrances, exits and hallways, campus-wide active shooter alarm systems that are separate from fire alarms, two-way radio systems, perimeter security fencing, bullet-resistant glass or film for school entrances, and door-locking systems.”

Districts across the state still have $7.2 million of the $99.6 million in school safety and security grant funding to spend, according to the Texas Education Agency’s spending.

“When we put up a 10th of a billion dollars in grant money to harden school assets, and that grant expires and there’s still millions and millions of dollars left in it, we’re scratching our heads wondering how is that the case,” Creighton said.

Districts still have until June 15, 2023, to spend the grant funding.

“If they’re not participating in many things that they themselves say they need, we’ve got some sort of a disconnect,” Creighton said. “When it comes to school safety, there is just no more important issue and we all should be working together to accomplish those goals yesterday.”