BY MANDI CAI AND JUAN PABLO GARNHAM AUG. 14, 2020

Austin officials slashed their police department’s budget this week as other Texas cities are rethinking how general fund dollars are spent — and whether spending so much to combat crime addresses the poverty that can cause it.

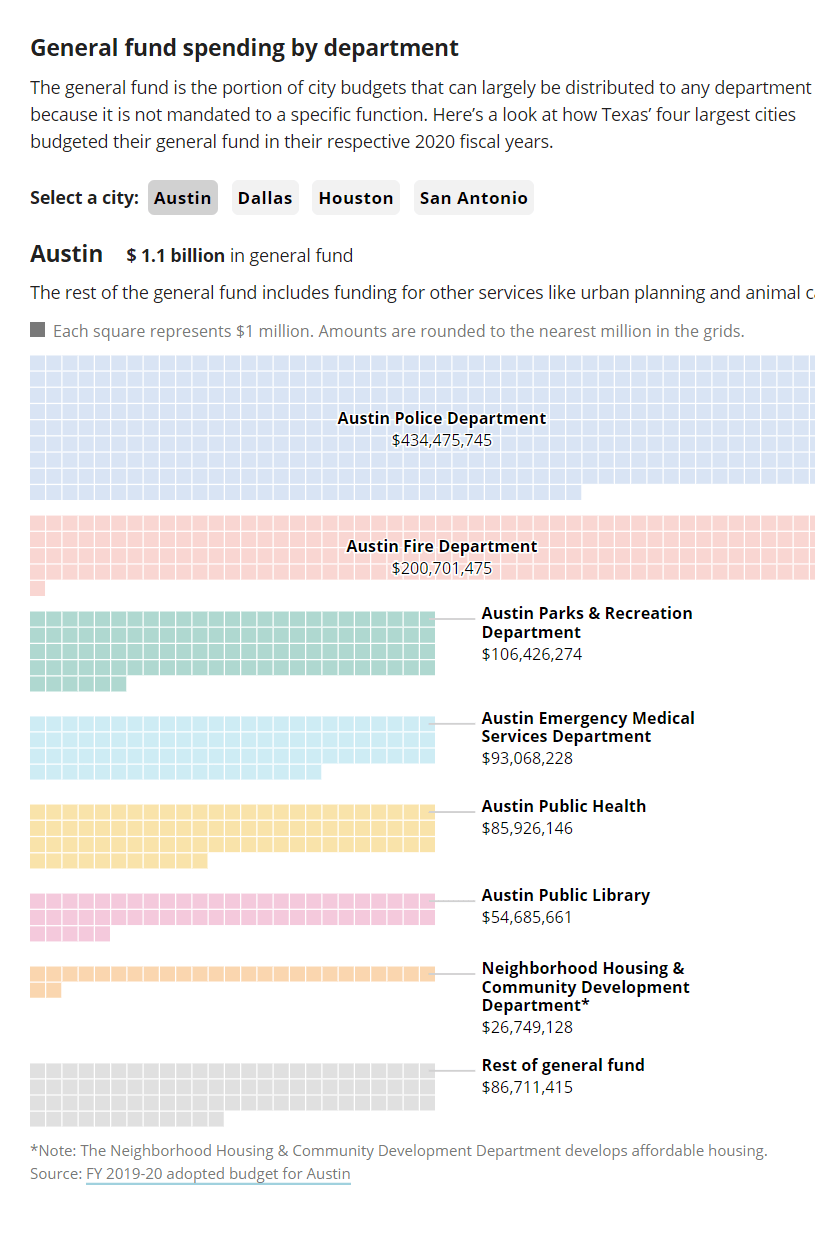

Officials in Austin, Dallas, Houston and San Antonio each spent more than $434 million from their general funds on their respective police departments during the 2020 fiscal year. For each, that was more than a third of their general funds, the portion of city budgets that can largely be distributed to any department because it is not mandated to a specific function.

Spending that much on police has rarely been challenged on a large scale, according to police reform advocates. But some Texas cities are rethinking how much they spend on police this year after the death of George Floyd, a Black man killed by Minneapolis police officers during an arrest, spurred protests against police brutality and calls to reduce police funding across the state and country.

On Thursday, the Austin City Council unanimously voted to cut its police department budget by one-third — or $150 million — over the next year.

Police reform activists like Nora Soto, the co-founder of Our City Our Future in Dallas, are asking City Council members to reallocate part of these funds toward areas like housing, social services and public spaces as part of an effort to end a history of discrimination, inequality and overpolicing of Black and brown communities.

In 2018, about a third of Texas prisoners were Black, a third were white and a third were Hispanic, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. That same year, about 12% of Texas’ population was Black, about 42% was white and 40% was Hispanic, according to the Texas Demographic Center.

Also in 2018, 19.6% of Black Texans lived below the poverty line, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, compared with 20.9% of Hispanic Texans and 8.5% of non-Hispanic white Texans.

“The only way that you’re going to prevent crime is by addressing the root causes of crime, and the main one is poverty,” Soto said. “Police have acted as a poverty patrol. They’re criminalizing poor people.”

Jennifer Szimanski, public affairs coordinator for the Combined Law Enforcement Associations of Texas, said funding that police departments receive is proportional to their responsibilities, which include everything from responding to potentially dangerous emergency 911 calls to attending monthly neighborhood meetings. And police unions like CLEAT have warned that cuts to public safety funding could increase crime.

“Just because of the sheer volume of tasks that we are responsible for dealing with, public safety is going to be the most expensive part of a city budget across the board. That’s really just demand,” Szimanski said.

Police department funding in Texas’ four largest cities

Texas’ four largest cities budgeted about a third or more of their general funds for their police departments in the 2020 fiscal year. Austin budgeted the most money per resident and largest share of its general fund on police. Houston, the state’s largest city, budgeted the largest total amount of money for its department.

| City | Police budget | Share of the general fund | Per resident |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austin | $434,475,745 | 39.9% | $444 |

| Dallas | $516,967,195 | 35.9% | $385 |

| Houston | $899,879,053 | 33.1% | $388 |

| San Antonio | $479,091,284 | 37.5% | $310 |

- Note: The amounts shown do not include funds or grants that are earmarked for particular purposes.

- Source: FY 2019-20 adopted budgets for Austin, Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio

Houston has the largest police budget in Texas and spent more than $899 million on police in the fiscal year that ended in June. But Austinites spent more on police per resident than their counterparts in the state’s three other biggest cities in the 2020 fiscal year before the City Council there slashed police funds in the 2021 budget. There, the city was budgeted to spend $443.84 per resident on police from its general fund in the 2020 fiscal year, which ends in September. The Austin Police Department also constituted 39.9% of the city’s general fund this fiscal year, a share that was larger than in Dallas, Houston or San Antonio.

According to Austin spokesperson Andy Tate, the high cost of living there drives officer’s wages up. The city also previously included many items in its police budget that other cities list separately, like park police and emergency communications centers. The 2021 Austin budget approved Thursday calls for approximately $20 million in immediate cuts, money that will be redirected to fund areas like violence prevention, food access and abortion access programs. Another $80 million in cuts would come from a yearlong process that will redistribute money used for civilian functions. About $50 million would come from reallocating dollars to a “Reimagine Safety Fund” that would divert money toward “alternative forms of public safety.”

The Houston City Council approved a minor funding increase to its police department in June, but an amendment that tried to redistribute some of the money to other areas, like the police oversight board and loans for businesses owned by Black and brown people, was rejected.

In San Antonio, the budget proposal presented on Aug. 5 includes raises for police officers and an $8 million increase in overall police funding. But it also cuts overtime and moves $1.3 million from the police department to the local health authority to create a new division of violence prevention, according to Texas Public Radio. This budget is scheduled to be approved by Sept. 17.

Dallas officials, who should vote on their budget by Sept. 23, are considering a proposal that doesn’t make large cuts to the police department, but adds $3.2 million for mental health services and increases housing, employment and other safety net resources.

Here is a look at how cities spent general fund revenues on police compared to other departments and initiatives in their 2020 fiscal year budgets:

It can be difficult to compare spending toward a goal, like decreasing homelessness or increasing workforce development because some cities may have an agency or a position dedicated to solve these challenges, while others have many departments contributing to the goal. Austin, for example, allocated $73.4 million toward homelessness, but a long list of agencies were involved in this effort, from public health to the design and delivery office.

Academic research has shown that hiring more officers can reduce crime. But experts and advocates say that spending a lot on public safety may also have negative outcomes, like overpolicing marginalized communities. At the same time, there’s evidence that shows that investing in areas like early childhood education or offering food stamps can also create safer neighborhoods. Police reform advocates said that policing is not able to solve deeper problems, as law enforcement mostly reacts to particular emergencies. Soto said, for example, investing in affordable housing is more important than funding police.

“Once you solve the issue of housing, you solve most of the issues that stem and that causes chronic poverty,” she said.

Szimanski said CLEAT doesn’t oppose more funding for other areas like mental health, as long as it doesn’t mean cuts to police departments.

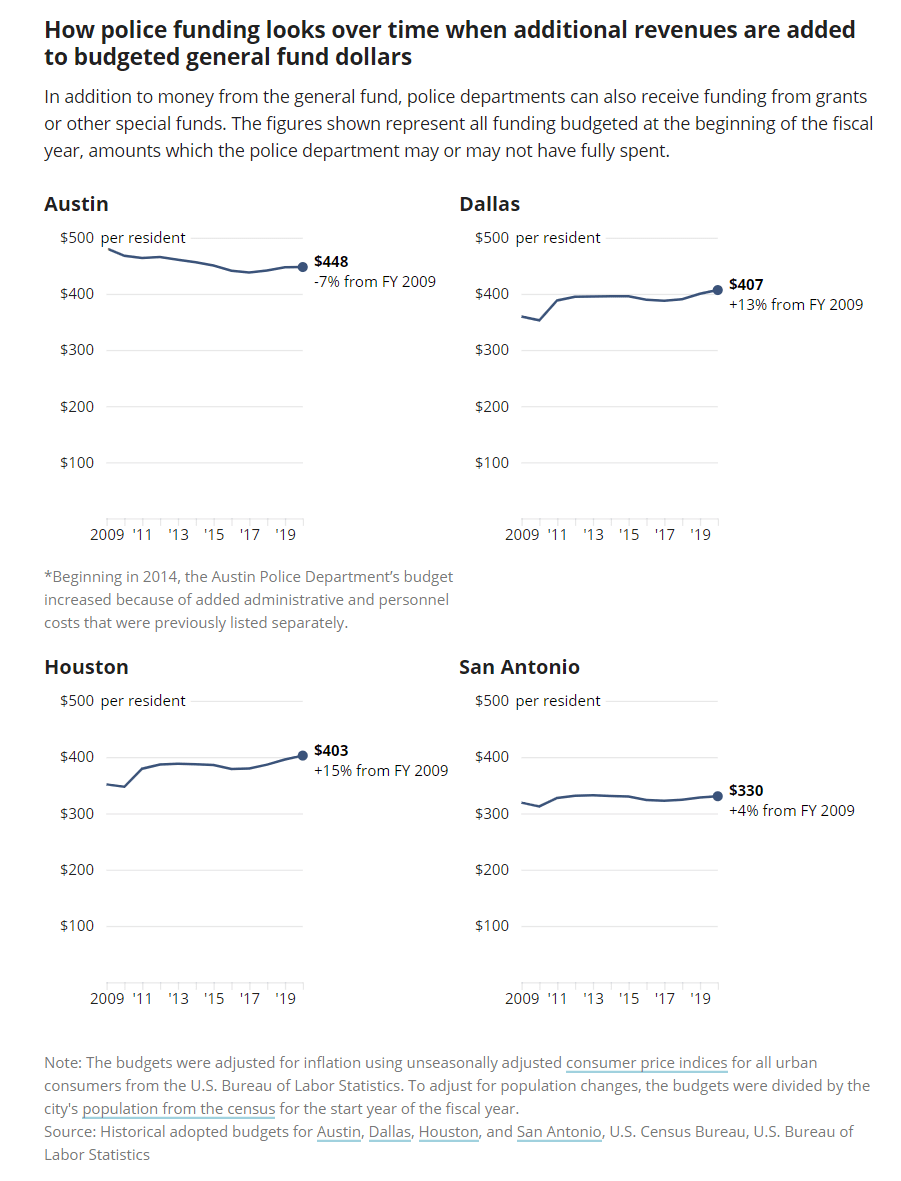

Although Austin just agreed to cut its police budget, Texas’ four biggest cities had previously mostly increased law enforcement funding overtime. But a per capita analysis of police spending shows that most of them were essentially catching up with the population growth. Still, Austin had a slight decrease in per-capita spending in recent years.

“The majority of that money is geared toward salaries,” said Alex Piquero, criminology professor at University of Texas at Dallas. “And those dollars are incrementally increased every year, especially when the departments are asked to hire more officers.”

Local leaders have tended to support increases rather than decreases in police funding. Even during economic crises, cities have been hesitant to lay off police officers.

“It is also a very labor-intensive item and they have a lot of equipment, which is expensive, too,” said Jennifer Doleac, director of the Justice Tech Lab at Texas A&M University.

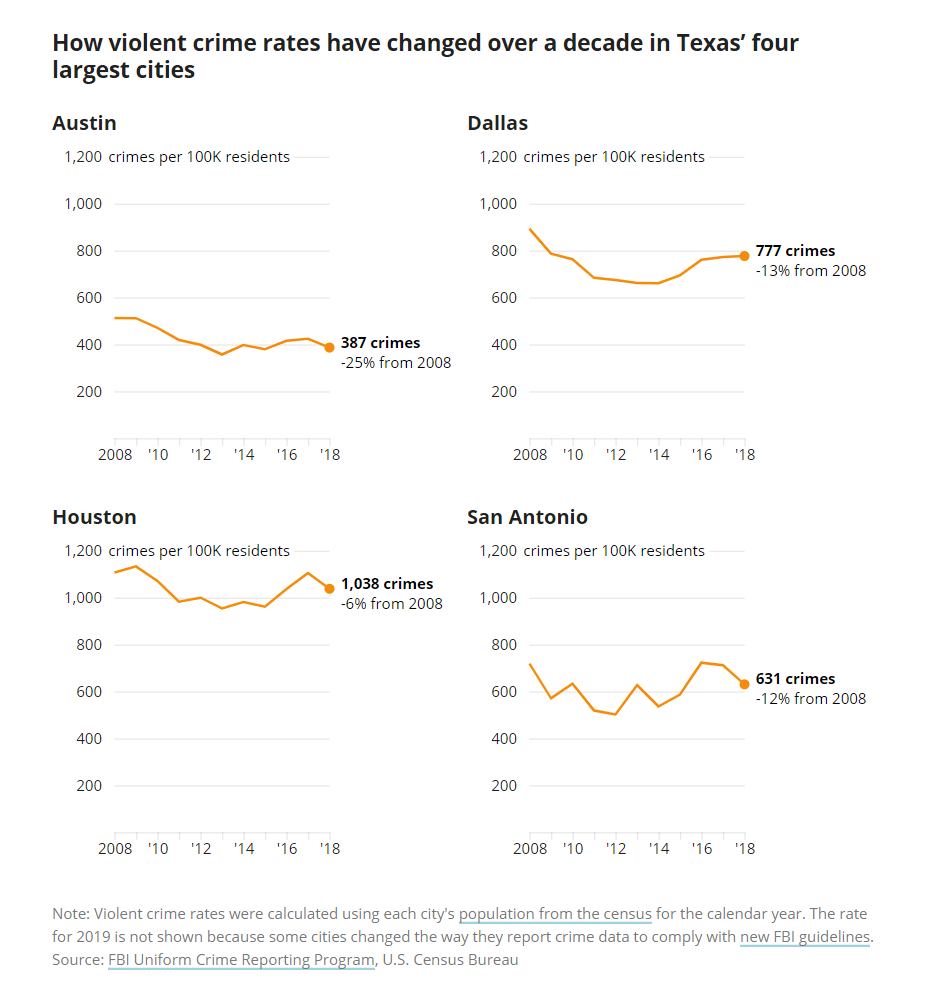

Between 2008 and 2018, according to FBI data, violent crimes have generally decreased in these four cities, although some cities have seen increases in specific years, like in Houston in 2017. Police union leaders have pointed out that the early data from 2020 shows increases in homicides and shootings in some cities, but the numbers are far below what they were 20 years ago.

Researchers say whether more funds decrease crime rates depends on how the money is used. For example, investing in data analysis and coordination systems has helped cities identify crime hot spots and target areas in need. University of California Irvine professor Emily Owens said that there has been “compelling evidence” that shows funding primary schools, public space improvements and employment for young people can lower crime rates.

“But local governments have been devoting fewer of these resources, specifically in places within their jurisdictions that are lower income and non-white,” Owens said.

It still is not clear that crime will increase if police funding is reduced or siphoned off for other areas.

“I think that remains to be seen, but if it does, it would really worry me,” Piquero said. “I can just envision a world where if you defund [police], cities are not going to take those monies and use them appropriately.”

Police representatives said that they believe the risk is not worth taking.

“If you have a budget cut, you’ll have less officers on the street, which means longer response times,” said Szimanski. “We believe that there’s absolutely going to be a spike in crime. If you go out and talk to people who live in certain areas that are typically high crime, that’s where you’ll find out that they immediately will be seeing the impacts.”

Meena Venkataramanan contributed to this report.